Cache Contents

![]()

Currency and banking during the Gold Rush was not regulated. Rapid growth coupled with the distance between California and established banking entities in the East resulted in local banks and assayers issuing varied forms of currency in the new territory. Coins were referred to as “slugs,” “tokens,” and “ingots.” Setting up a federal mint on the West Coast proved difficult initially for political and logistical reasons, so these private firms continued to meet demand by striking their own coinage for California pioneers even after the San Francisco mint opened in 1854.

One of the more interesting aspects of this era was the sinking of the SS Central America (“The Ship of Gold”) during a hurricane in Sept. 1857 off the coast of South Carolina. The steamer was carrying 578 passengers and approximately 9 tons of gold prospected in California during the Gold Rush. 477 passengers perished in the tragedy. The loss of the vessel started the economic Panic of 1857. The shipwreck was first located in 1988 at a depth of 7,200 ft. It is estimated that $100-$150M of gold has been recovered from the site via deep water salvage, much of it in federal and territorial gold coinage struck in San Francisco.

Below are detailed notes on the historical replicas and facsimiles you will find in the treasure box!

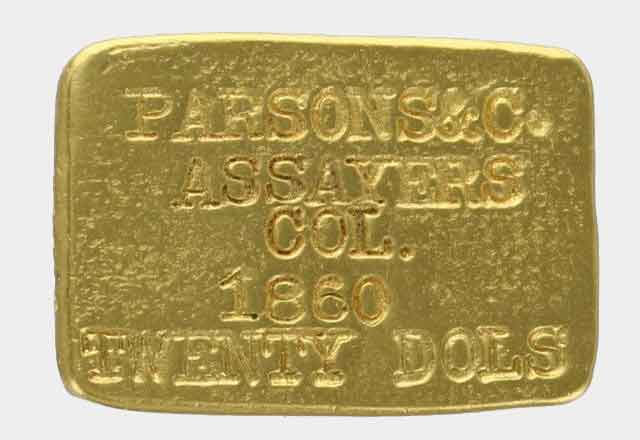

Miners would deposit their bullion with an assayer and in return receive a written receipt listing the assayers’ inventory identification number and documented weight of the deposit. Then, over the period of 24 hours, the assayer would refine out the impurities of the bullion deposit and pour the remains into a mold that corresponded to the lot size. The assayer would clip off the end as his fee and use the clipped piece to determine the purity. The precise weight and fineness were then stamped on the bar along with the unique serial number and a dollar value. Monetary ingots were prone to fraud because of how easy it was to shave off the ends, ending up with bars that did not correspond to their stamped value.

California gold coinage were privately issued coin-like tokens used in place of official currency during the gold rush in California. Referred to as “fractionals,” many of these tokens had a stated tender but some of them didn’t. They were valued in fractional amounts and had approximatly 80% of the correct weight of gold in them. They were too small to handle for everyday use, but proved to be valuable as economic souveniers that could be sent back to family members in the East.

The 1849 $5 Norris-Greg “half eagle” was probably the first example of a privately issued territorial gold coin during the Gold Rush. It was struck at Benica City north of San Francisco. Norris and Greg were members of a New York engineering firm who specialized in the manufacture of pipes and fittings. It is not known when they ceased operations.

The 1850 $10 Baldwin & Co. “49er horseman” is tied to an interesting tidbit. The firm was advertised as a jeweler and watchmaker in San Francisco on the Clay Street Plaza. They were one of the first organizations to widely strike low denomination coins at $5, $10, and $20. The were embroiled in controversy during the “Gold Swindle” after Baldwin’s $20 coin was found to only have $19.40 worth of gold. This led to their eventual demise due to a lack of public confidence.

The 1851 $50 Humbert “quintuple eagle” gold slug was produced by Moffat and Company under the direction of Augustus Humbert, a former watchmaker commissioned by the U.S. treasury to establish the U.S. Assay Office of Gold. This operation was run prior to the establishment of the official U.S. mint in San Francisco in 1854. His octagonal ingots (locally called “adobes” because they were as “heavy as bricks”) were the largest ingots minted during this era weighing in at 2.5 oz. These ingots were originally struck in a temporary mint east of San Jose at Mount Ophir before official mints were established. Not popular at the time due to their sharp edges, the Humbert is one of the most prized ingots sought today by collectors because of its rarity and size. At auction, they can range in value of $10,000 and up. The finest examples have sold for $500k a piece. There were 13 original slugs recovered from the SS Central America that were likely destined for Philadelphia to be melted into Federal coinage.

The 1854 $20 Kellogg was struck by the private firm of Kellogg & Co. John Glover Kellogg originally worked for Moffat & Co., and was persuaded by local banks to strike local slugs until the U.S. mint opened in San Francisco after the U.S. Assay Office of Gold ceased operations in 1853. He set up shop in the basement of J. P. Haven's building on Montgomery Street in downtown San Francisco. The integrity of his work was endorsed by Augustus Humbert, the former U.S. Gold Assayer. The Kellogg coins were identical to the federally issued Liberty Head “double eagles” of the day, except the word “Kellogg” appeared in the headdress instead of the word “Liberty,” and the word “California” appeared on the reverse side of the coin instead of “United States of America.” Kellogg claimed his firm could issue $20,000 worth of coinage each day. The mint in San Francisco struggled to meet coinage demand for the first 5-6 years, so local California banks continued to use Kellog & Co. to mint coinage until 1860.

The 1855 $50 Wass-Molitar was a large terriorial slug struck by Hungarian immigrants Samuel C. Wass and Augustus P. Molitor at their privately run mint in San Francisco. Relief detail in this coin was second-rate because of how quickly they were struck. This coin was heavily circulated by pioneers as local currency during the Gold Rush, so very fine examples are essentially non-existant today. Miners could bring in nuggets and gold dust and have them struck into coins within 48 hours of deposit. Most of these coins were eventually melted down at the San Francisco mint and made into Federal coinage.

The $20 Liberty Head “double eagle” is the gold coin standard-bearer of the United States treasury during this era. These coins contained approximately 90% of their weight in gold. They were first minted in 1849 (Type 1) in Philadelphia which coincided with the California Gold Rush. In 1866 the motto, “In God We Trust” was added in response to the country’s internal division wrought by the American Civil War. These are referred to as the Type 2. The Saint-Gaudens double eagle eventually replaced this design at the beginning of the 20th century. An “S” under the tailfeather indicates it was minted in San Francisco. Much of the gold recovered from the SS Central America were double eagle Liberties.

The 1877 $50 Half union was minted by the United States as a pattern and never circulated. Considered one of the most recognizable and significant patterns in the U.S. Mint’s history, the design was similar to the $20 Liberty Head “double-eagle” minted and circulated during the same period. Only two specimens of the Half union were ever struck in solid gold and both of them belong to the Smithsonian. No others are known to exist (except in this cache). There was a commemorative version released in 1915 to celebrated the Panama-Pacific exposition in San Francisco.

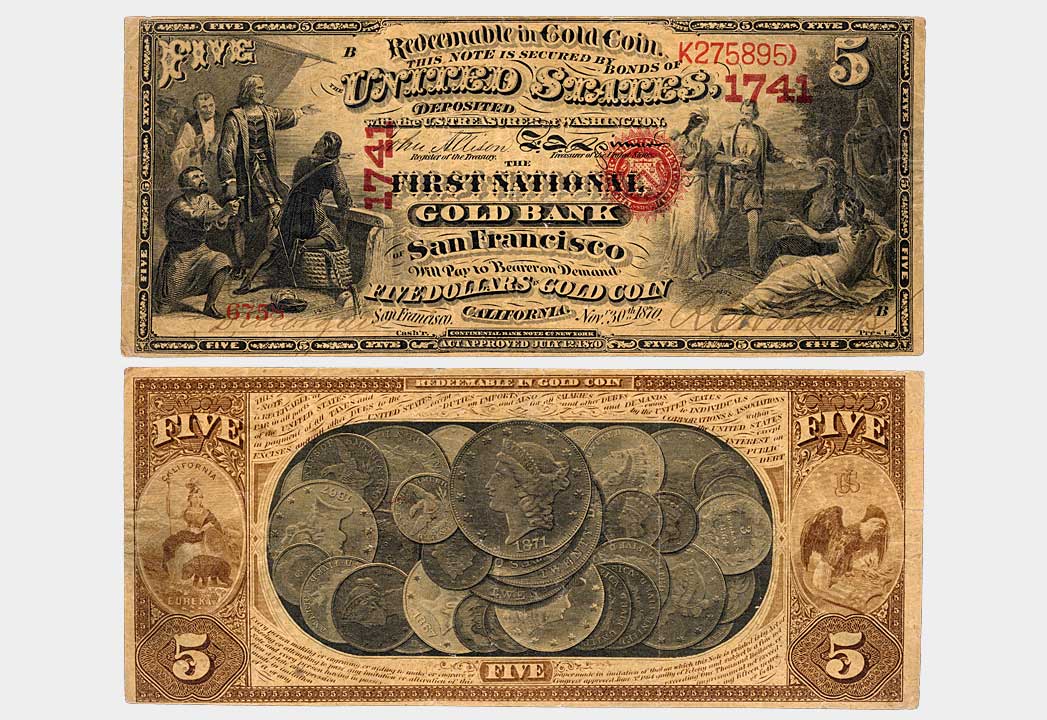

Nine national “gold banks” were chartered in the San Francisco Bay area in the 1870s -1880s. They issued yellow-tinted National Gold Bank Notes in six circulated denominations ($5, $10, $20, $50, $100, and $500). These notes are prized by collectors today as there are only around 600+ still known to exist (until now, of course, as another 100+ have been added to the worldwide total after discovery of the Bandido Gold cache).

The U.S. Treasury also released gold paper currency during this period but these notes are more commonly referred to as U.S. Gold Certificates.

Wells Fargo & Company was established in 1852 to provide express and banking services in California. They issued Certificates of Exchange in connection to gold deposited with them. Three copies of each certificate were generated and transported by three different carriers between remitters and receivers in the East and West due to the uncertainity of early transportation. The first copy of the certificate to arrive was treated as official and the others were then voided.

A Mexican officer by the name of Andres Castillero was the first to form a stock company related to the Almaden Quicksilver mines. In 1845 he divided the mine into 24 shares. In 1846, Barron, Forbes & Co., of Tepic, Mexico, became the principal stockholders. Furnaces were constructed in 1850, but an injunction was filed as the true value of the mine became apparent. In 1864 the company sold everything for $1.7M to a company chartered under the laws of New York and Pennsylvania, The Quicksilver Mining Company. Stockholders never really saw much of a return on investment because of the high cost of operations and labor.